September. All rage, no runways.

There’s a kind of fashion that doesn’t live in your typical storefront windows or your average sponsored posts.

It’s the cotton shirt you pulled from a dye pot in your kitchen sink.

The jacket patched so many times the repairs are the design.

The bolt of fabric leaning in a studio corner, rescued from a warehouse clear-out.

It’s not about running from trends or lecturing anyone about fast fashion’s failures — we’ve heard that sermon. I wrote about it here. This is about the materials we live in, the hands they pass through, and the ways we can make them more ours.

How We End Up in Our Clothes

Fast fashion is cheap, but the cost is brutal. Rivers are dyed the colour of trend cycles. Workers are paid starvation wages (if they’re paid at all) and forced to work in deplorable conditions, often in unsafe environments. Synthetic fibres shed microplastics into every load of laundry until we’re all coughing up polyester dust. And for what? A fit check that disappears into the scroll?

It’s violence in a new shade every season.

Whether you know it or not, the average shirt has been on more planes than you have. Cotton picked in one country, spun in another, woven in a third, dyed in a fourth, cut and sewn in a fifth. At each step, someone chose the fibre, the weave, the finish, the colour, the batch size.

It’s a machine designed for speed, waste, and dependence. It thrives on:

- Overproduction: Clothing made in excess, regardless of need.

- Planned obsolescence: Garments designed to break down, stretch out, or lose shape fast.

- Global harm: Synthetic dyes that poison rivers, polyester microfibres in every ocean, and workers earning less than survival wages.

In mass production, those choices lean toward speed, uniformity, and price. That’s how you and a stranger halfway across the world can buy the same blue button-down, identical down to the stitch length.

Outside that system, the starting point is different. You work with what you have, or what brings you joy: a stack of onion skins, a roll of deadstock linen, a quilt too worn to stay on a bed but perfect to turn into a jacket. The “limitations” become the style.

We don’t need to reform this system. We need to starve it.

Why Colour Deserves Its Own Story

One of the biggest — and least visible — decisions in that chain is colour.

It’s easy to take for granted: you want blue, you buy blue. But the way that colour gets into the fibre is an entire world of its own, with its own history, technologies, and environmental footprint.

Dyeing is where science, craft, and place meet. It’s where clothing moves from raw material to something you can imagine on your body. And the path from pigment to finished garment has changed more in the last 200 years than in the thousands before.

From Cave Pigments to Chemical Colour

Dyeing fabric isn’t new. It’s one of the oldest human arts, older than most recorded histories.

Indigo blues from India, Africa, and Japan.

Madder reds from Europe and Asia.

Weld and saffron yellows.

Cochineal crimson from tiny beetles in Central and South America.

For most of that history, colour was tied to place and season. The plant you grew, the water you had, the hands that knew how to coax pigment into cloth.

Then in 1856, an 18-year-old chemist named William Henry Perkin accidentally invented mauveine — the first synthetic dye. Within decades, synthetics dominated. They were bright, cheap, colourfast… and often toxic to waterways and workers. The connection between colour and its source broke.

Natural dyes never vanished. They just moved out of the factory and into smaller studios, workshops, and kitchens.

Natural Dyes Today

Forget chemical vats and synthetic pigments that leach into ecosystems. Natural dyes made from plants, minerals, even rust, are turning rebellion into ritual. Avocado pits, onion skins, marigold petals, black beans. Your compost bin is a palette. Your boiling pot is an altar. And no two pieces ever come out the same.

It’s not about precision. It’s about process. Slowness. Experimentation. Learning from the plant world instead of conquering it. And honestly? Watching a cotton tee take on the shade of your backyard dandelions hits way harder than anything sold under stadium lights.

In 2025, natural dyeing is part tradition-keeper, part experimenter.

- Tradition: Aboubakar Fofana’s fermented indigo vats in Mali and France. Japanese aizome dyers tending sukumo like it’s a living thing.

- Experimentation: Kitchen mordants like soy milk, iron water made from rusty nails, bundle-dyeing with foraged leaves.

The draw? Variability. The same plant can dye a pale gold in May and a coppery orange in October. A scarf dyed with marigolds from your own yard isn’t just yellow — it’s that yellow, from that plant, in that season.

Kitchen colour to try:

Onion skins → gold to rust

Avocado pits → blush to mauve

Black beans → slate to denim blue

Red cabbage → violet to teal (pH-dependent)

Natural dyeing doesn’t try to imitate the uniformity of synthetics. It celebrates the opposite: a colour that shifts with the light, the fibre, and time.

And once you’ve fallen in love with colour, the next question is: what fabric are you putting it on? That’s where deadstock comes in.

Deadstock: The Industry’s Overflow

Deadstock is what’s left after the industry’s “just in case” ordering. Extra rolls of wool, silk, cotton, linen that never make it into production — sometimes hundreds of metres. That’s before the wastage of manufactured deadstock that goes unsold from the manufacturer. It’s not pure sustainability (it’s born from overproduction), but in small hands, it’s opportunity.

Deadstock means:

- Access to quality materials without the footprint of new manufacturing.

- Scarcity that shapes the design.

- Prints and weaves that aren’t in current mass circulation.

Example: Montréal designer Eliza Faulkner builds part of her line around deadstock. A print might appear on a dozen dresses and then disappear — not as hype, but because the fabric is gone.

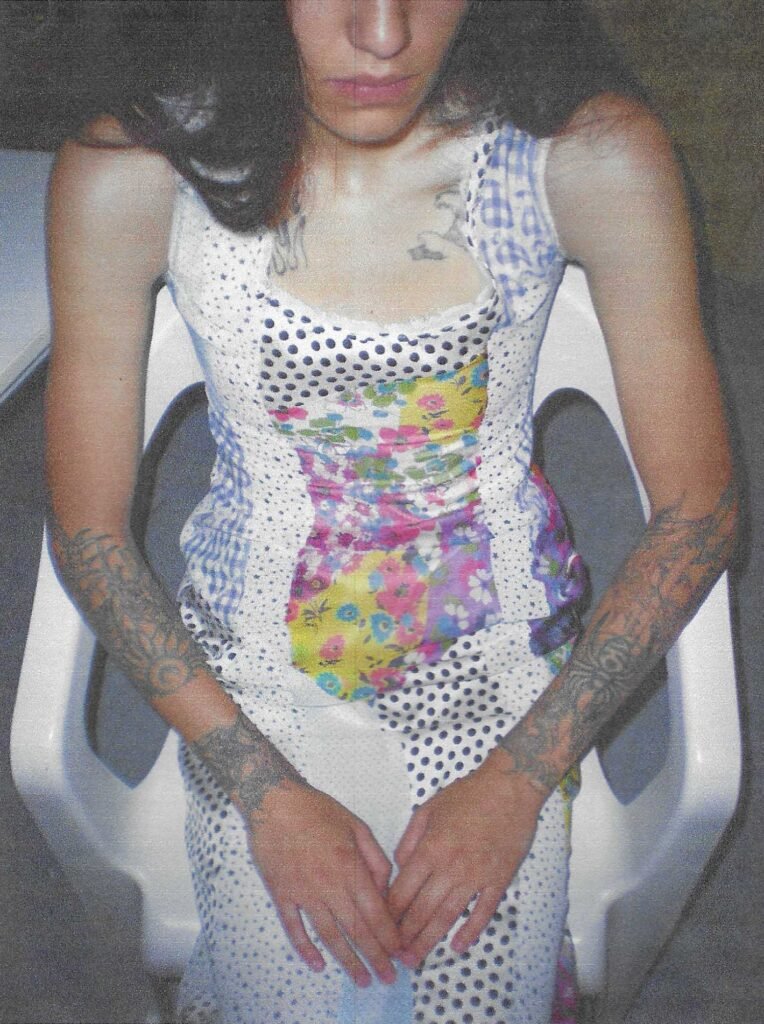

Dirtbag Couture: Imperfection as the Point

Welcome to the era of Dirtbag Couture — where seams don’t match, fabric comes from Facebook Marketplace and estate sales, and every piece is a middle finger to mass production.

The heroes of this aesthetic? People working out of basements, community print studios, and crowded kitchen tables. People who know how to sew, dye, mend, and hack their way into fashion systems that were never meant to include them. Sometimes ugly. Sometimes genius. Always alive.

Once, a visible mend meant you couldn’t afford to hide it. Now it can be the most interesting thing about the garment. “Dirtbag couture” — a half-joking name — is what happens when you piece together offcuts, scraps, and found fabric without pretending they were always meant to match. This isn’t “aspirational.” It’s post-capitalist patchwork. (Mmmm, patchwork!!!)

Not trying to look “luxury” — but may cost more due to labour.

The label started showing up in climbing/outdoor circles, but has since been adopted by makers blending punk DIY with slow fashion values.

Think:

- Zero Waste Daniel in NYC, making bold geometric panels from post-consumer scrap.

- Carleen in California, turning vintage quilts into coats without erasing their history.

- Absolute Rubbish in Toronto, building garments from upcycled textiles and offcuts from the designers she serves.

And definitely check out Future VVWorld — a digital editorial platform spotlighting sustainable fashion, footwear, and design innovations from around the globe.

Platforms like Future VVWorld show what happens when ideals and aesthetics actually match — and dirtbag couture is proof you don’t need a glossy runway to pull it off.

Dirtbag Couture isn’t anti-fashion because it hates clothing. It’s anti-fashion because it refuses to serve the system that weaponized clothing against workers, the environment, and the people who can’t or won’t buy in.

Anti-Trend Is the Trend

Trends demand amnesia. They ask you to forget what you loved last year so you’ll buy again this year.

Anti-trend is the opposite. It’s wearing the same silhouette for a decade. It’s mending jeans until the fabric becomes a living record of your life. It’s committing to your taste — not the algorithm’s.

The future of fashion isn’t seasonal. It isn’t cohesive. It isn’t clean. It’s full of holes, hand-stitching, visible mends, inside jokes, repurposed fast fashion, embroidery as protest, sleeves made of tablecloths, and jackets that smell like woodsmoke. It’s modular, layered, dirty, emotional. It’s for the girl in the audience who made her own shirt and sewed lyrics inside the hem.

You don’t have to wait for an invite. You don’t need permission. You don’t need new.

People doing awesome things with fabric is my favourite rabbit hole on the internet. Check out some of these designers who are truly doing awesome things.

Canadian Makers & Designers

- PAR ICI Jewelry (Toronto) – Recycled metals, season-less design.

- Maiwa (Vancouver) – Education, retail, and dye studio bridging tradition and contemporary design.

- Anne Mulaire (Winnipeg) – Métis-owned, zero-waste, regenerative.

- Le Point Visible (Québec) – Graphic quilts and quilted garments from offcuts.

Global Rebels

- Bethany Williams (UK) – Waste textiles + social impact collaborations.

- GARBAGE Core (Los Angeles) – Maximalist salvage garments.

Dye & Textile Artists

- Aboubakar Fofana (Mali/France) – Indigo master, working entirely with natural processes.

- Maiwa School of Textiles (Vancouver) – Natural dye education and activism.

- Sasha Duerr (California) – Seasonal dye practice, rooted in local ecology.

Start Where You Are

I know that you’re inspired after checking out some of these makers and their OOAK creations. Well, you don’t have to be a designer with a dedicated studio to work like one. Every technique the pros use — from custom dye baths to inventive upcycling — has a kitchen-table version. The difference is scale, not magic.

Natural dye, mending and upcycling isn’t just craft. It’s political. It demands patience. It teaches resourcefulness. It asks you to work with what’s available, not what’s mass-produced.

TOOLKIT FOR SLOW CLOTHES MAKING

The basics you’ll actually use — no fancy gadgets required.

Getting started? Boil some onion skins and throw in an old cotton tee. Make a Sashiko sampler to mend that hole in your jeans. Cut up your old clothes before sending them to landfill and experiment!

Source like a stylist: Designers score deadstock from warehouses; you can thrift linens for yardage or ask local makers if they have offcuts. Most are happy to pass materials along — it keeps good fabric out of landfill and builds community.

Upcycle like a label: Sleeve swaps, hemlines chopped and reimagined, a placket in a surprising colour — these aren’t just runway tricks. They’re ways to make your clothes your own, using the pieces you already have.

The point isn’t to replicate a collection — it’s to tap into the same creative energy. You can start tonight with a needle, thread, and whatever’s in your laundry pile.

Why It Sticks

Clothes made or altered this way hold their place in your wardrobe. They accumulate meaning. You remember the day you dyed that shirt. The trip where you tore those jeans and the night you fixed them. The stranger who asked about your patched jacket at the grocery store (the best).

It’s not about rejecting modern fashion wholesale. It’s about valuing the pieces that carry your story — and giving them the time, care, and skill to last.

Looking Ahead

The most interesting corners of fashion now are where old skills and new materials overlap. Regenerative fibre farming alongside bio-based textiles like mycelium leather. Deadstock runs mixed with plant-dyed silk. Small-batch studios teaching repair, quilting, and colour work to the next wave of makers.

In that mix, the real currency isn’t trend forecasting — it’s material literacy. Knowing how fabric behaves, how to coax colour into it, how to keep it going.

The Last Word

Fashion isn’t inherently the enemy. But the system that controls it is. The antidote isn’t perfection — it’s persistence. Make things. Keep them. Pass them on. Let your clothes tell the truth about where they came from and who made them.

The best clothes aren’t always the newest or the most “on trend.” Sometimes they’re the ones you’ve kept the longest, because they fit your life and not just your body. The shirt that fades, the coat that softens, the trousers that wear in, not out.

Make them. Find them. Keep them. Let them change with you.

What We’re Doing About It (And Why We’re Not Perfect)

At She Zine Mag, we’re not pretending to be saints. Our shop is launching soon, and yes, some of our merch has polyester blends. Some of our zine covers get printed on glossy paper because it’s what we can afford. But we’re always asking: how do we do better? This means printing in-house, sewing with found fabrics, and launching our own lines of handmade goods that actually mean something.

We also talk openly about the environmental toll of digital tools. Transparency isn’t optional if you’re serious about accountability.

A Toolkit for Fighting Back

You don’t need a degree in fashion design to join in. You need curiosity and resourcefulness.

Here’s your starter kit for Dirtbag Couture and creative rebellion:

- Dye something – Start with onion skins, avocado pits, or black beans.

- Shop weird – Estate sales, free piles, Buy Nothing groups.

- Mend visibly – Let the repairs become part of the design.

- Share your process – Zines, blog posts, TikTok tutorials.

- Make zines about it. Document your process. Share your fuckups. Start a style archive for the girls who never felt seen in fashion spreads.

- Join the crew. The New Girl Army is always recruiting. Come hang with us. Share your work. Build something weirder together.

- Connect – Join local maker spaces, dye circles, or mending meetups.

This isn’t a trend. It’s a movement. And you’re already invited.

Subscribe to The Edit for more dispatches from the fashion underground

Pitch us your handmade fashion stories

Tell us what you’ve sewn, dyed, hacked, or upcycled lately

→ Subscribe to The Edit

→ Submit Your Work

→ Meet the Team (some of us aren’t real… on purpose)

→ Follow @shezinemagazine

AXO (she/her) is a multidisciplinary creator, editor, and builder of feminist media ecosystems based in Toronto. She is the founder of She Zine Mag, Side Project Distro, BBLGM Club, and several other projects under the AXO&Co umbrella — each rooted in DIY culture, creative rebellion, and community care. Her work explores the intersection of craft, technology, and consciousness, with an emphasis on handmade ethics, neurodivergent creativity, and the politics of making. She is an advocate for accessible creativity and the power of small-scale cultural production to spark social change. Her practice merges punk, print, and digital media while refusing to separate the emotional from the practical. Above all, her work invites others to build creative lives that are thoughtful, defiant, and deeply handmade.