A memoir of periods, silence, survival, and the hug I wish I could send across decades.

Trauma exists in the context of your own life and situation. So what does that mean? If we think about trauma in the context of North America, it means bad sex ed, Catholic shame, and being left to piece together the story of my own body from commercials and whispers.

But zoom out, and the picture gets even darker. In Nepal, menstruating girls are still banished to sheds — small, unsafe structures where they spend days alone, exposed to cold, smoke, or snakebites. In rural India, women are barred from kitchens and temples, treated like their bodies are contaminating. Across the globe, period poverty forces people to miss school or work, to improvise with rags or newspaper, or to choose between food and tampons.

This isn’t biology. It’s violence disguised as tradition or tolerated as neglect. Period violence. The kind that punishes you not for what you’ve done, but simply for bleeding.

And yet, there’s resistance. Scotland passed a law guaranteeing free menstrual products in schools and public buildings. Activists in dozens of countries are dismantling tampon taxes. Grassroots groups are distributing reusable pads and menstrual cups to make sure no one bleeds in shame.

And that’s the thing about trauma: it scales. From a girl in a shed in Nepal to a girl in Canada staring at a bathroom garbage pail, the details differ but the weight is the same — confusion, shame, abandonment. Nobody told us what was happening. Nobody gave us the words. So we were left to make sense of it on our own.

Improvisation and Survival

For me, that meant entering puberty with about a third of the education I needed from school, and zero from home.

Because I didn’t talk about periods with my mom, I didn’t want her to notice her stockpile of maxi pads slowly diminishing. So I found the cloth diapers that my mom had used on all four of her children when we were babies. I folded them into the shape of a pad and hoped to God they wouldn’t tumble out of my pant leg walking down the halls at school. It felt like a kaiser roll in my underwear, and I’m positive it must’ve looked like I had shit my pants. I could feel people noticing — teachers, classmates — but no one ever said anything to my face. So I guess I thought I had gotten away with something. I would race home after school, having made it one more day without detection. Then I would wait for my family of six to be out of our one bathroom long enough for me to covertly wash the cloth diapers, sneak them back into my room, roll them in bath towels, and hide them under my bed to dry. When I couldn’t find an opportune time to do my dirty laundry, I would stash them in the box of my flower press kit in the top of my closet. This went on for that first year of my period, at least.

Confusion and Silence

My mother kept her maxi pads in a bathroom cabinet and so, had I been ballsy enough, I could’ve helped myself — but I wasn’t and I didn’t. Commercials at the time were incredibly vague and aside from “one day you’ll bleed and bleeding means babies,” school was essentially useless.

I had thought that maxi pads were for women who peed themselves and only learned that they were for blood when I unwrapped one of the toilet rolls in the bathroom garbage that would mysteriously appear once a month. At that time I still didn’t know what that could mean, so I was left to assume that someone in the house was probably dying and didn’t want to tell us about it.

The Classroom That Made It Worse

We didn’t have health class at my Catholic elementary school. For a week in grades six, seven, and eight — a week we all dreaded — we endured a 30-minute period with our teacher nervously hovering a pen over poorly photocopied transparencies of anatomical images of penises and vaginas.

I remember feeling especially horrible for my sixth-grade teacher. You could clearly see his spittle spray onto the transparency, smudging the notations he’d scribbled onto the images (“penis goes here, sperm travels here, and the blood!! Oooooh the blood… not literally, but you get it”), the shadow of his marker visibly trembling in the projected image being broadcast onto the chalkboard. He was one of my all-time favourites, and he was so obviously uncomfortable with the subject matter.

Grade seven, the lesson came from the same male teacher who would request only the girls wear white T-shirts for gym class at our non-uniform school — who also would occasionally wander into the girls’ bathroom while we were changing. I remember me and all the other girls in my class looking at each other and all of us knowing very clearly that it was wrong. Nothing ever happened, so I’m assuming that none of us ever told, but yeah — now this guy is telling me what’s going on with my vagina. It sucked.

I don’t know if it was a sentiment shared by my female classmates, because at the time I don’t know if any of us had the language to express how we felt. To each other or anyone else. So there we sat in a situation that I look back on as wholly inappropriate — putting us in the position where a man who was already pushing the line of what was appropriate with young girls could legally and with permission talk to us about our maturing sexual organs.

First Blood

I was very unpopular during the years that I was at this school and I felt specifically targeted by this teacher. Now, with almost three decades of hindsight behind me, I can’t help but wonder if I was the only student who felt targeted.

I think I experienced my first period when I was near the end of grade 7, perhaps the beginning of grade 8. Thinking back on that time to create this post makes me feel incredibly uncomfortable. There are lots of days when I feel awful as an adult, obviously, but when I sit here reflecting on how I felt during this time of my life I really feel desperately sad for that little girl.

And I’ll give her credit — I think things truly were as bad as they seemed, and I really wish so much that I could give that little girl a hug. It makes me want to run out into the world and give that hug to another girl who might be struggling today. If you’re that girl reading this right now, then I really hope that you’ll accept my virtual hug and know how much I mean it and know that I understand.

Reflection and Resilience

I’m not going to tell you that everything’s going to get better, even if I believe that to be true. If you get “stuck” dreaming about the future, then you might find yourself drowning in today. So I’ll be cliché and tell you to live in the now.

When I was existing in the space I’ve described in this post, I really felt stuck, ignored, perhaps even abandoned. With nowhere to go and no one to talk to, I spent a lot of time focusing on coping strategies. At the end of each day I would reflect upon the day’s goings-on and evaluate how I dealt with whatever I might’ve faced. Some days I’d have a win, some days were just shit, but either way I’d find ways to feel proud of myself for being so strong and so brave to have made it through another day.

Childhood and puberty don’t go by in a flash. They will probably feel like a never-ending grind (and you’ve got hormones reinforcing this point of view, so it’s not just in your head). But once it’s over, your suffering and your ability to make it through each day will have equipped you to deal with all the other “life stuff” that will come at you as an adult.

One thing that helped me to cope and really made me feel strong on all the days that were especially difficult was my ability and fucking determination to be kind. It’s something I still practice today and is still not always easy to do. Basically my motto goes like this:

“None of these assholes are going to turn me into a bad person.”

But kindness isn’t a shield. It didn’t erase the confusion or the shame I carried. What it did was give me something to hold onto when everything else felt shaky. It reminded me that I could choose who I was, even when no one around me was giving me choices about my own body. That’s still true now: the practice of being kind is messy, imperfect, and exhausting sometimes, but it’s also a kind of rebellion. If silence and stigma were handed down to me, then compassion is what I decided to hand back.

Closing

Even if I can’t go to that girl in grade seven, but I can send something to her now: a hug stretched across decades. I can imagine her shoulders finally relaxing, her fear softening just enough to feel safe. And if you’re reading this, and you’ve ever felt small or abandoned in your own body, the hug is for you too. It’s clumsy and invisible, but it’s real.

I don’t have easy wisdom to offer. Life doesn’t get neat, but it does get wider. You grow more room for yourself. You learn to name the things no one named for you. And you start to see how strong you always were.

If I could tell that girl anything, it would be: you’re not cursed. You’re not broken. You were always enough.

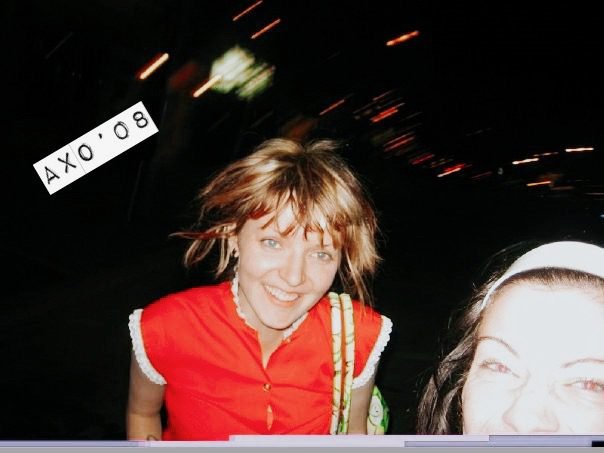

AXO (she/her) is a multidisciplinary creator, editor, and builder of feminist media ecosystems based in Toronto. She is the founder of She Zine Mag, Side Project Distro, BBLGM Club, and several other projects under the AXO&Co umbrella — each rooted in DIY culture, creative rebellion, and community care. Her work explores the intersection of craft, technology, and consciousness, with an emphasis on handmade ethics, neurodivergent creativity, and the politics of making. She is an advocate for accessible creativity and the power of small-scale cultural production to spark social change. Her practice merges punk, print, and digital media while refusing to separate the emotional from the practical. Above all, her work invites others to build creative lives that are thoughtful, defiant, and deeply handmade.