The Doll That Wouldn’t Stay Dead

In the early ’70s, the toy aisle was a pink fever dream.

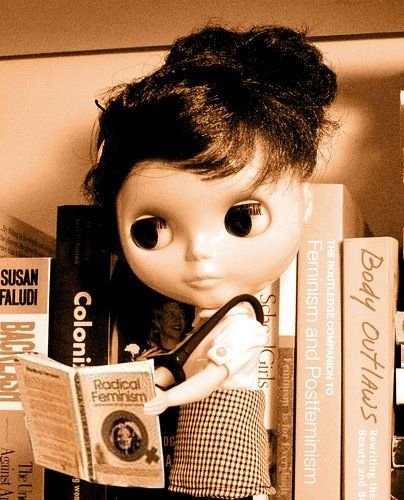

Rows of baby dolls waited to be fed, burped, and gently rocked to sleep. Little girls learned early: care for it, cradle it, and smile pretty while you do it. Then, in 1972, something strange appeared among the soft pastels — a doll with a head too big for her body and eyes that clicked through colours like a mood ring possessed. Her name was Blythe, and she scared the living daylights out of parents everywhere.

Kenner Toys thought she’d be a hit. Instead, they got complaints. Kids cried. Moms shuddered. Dads probably muttered something about nightmares. Within a year, she was yanked off shelves and quietly buried in the toy-box graveyard.

But the thing about failed girls — the ones who get called too weird, too ugly, too much — is that they have a habit of crawling back.

Blythe’s story didn’t end in the ’70s. She went underground, then overseas, then online, where she became something bigger than a toy: a symbol of creative rebellion, feminist reclamation, and the sheer weird power of not fitting in.

“Blythe didn’t fail because she was ugly. She failed because she didn’t behave.”

Part I: A Market Failure with Too Much Personality

Let’s rewind.

Blythe was created by Allison Katzman, a toy designer working for Marvin Glass & Associates — the same group behind Lite-Brite and Mr. Machine. Katzman had already designed successful toys, but Blythe was different. She wasn’t pretty in the traditional sense. She wasn’t sweet or soft. She was strange.

Kenner Toys released four different Blythe dolls, each with a pull-string mechanism that rotated her eyes through blue, green, pink, and orange, and shifted her gaze. It was innovative. It was artful. It was… apparently terrifying.

Kids didn’t know what to do with her. She wasn’t babyish like a Cabbage Patch Kid, nor glamorous like Barbie. Her unsettling proportions made her look like a cross between an alien and a mod fashion sketch.

Parents called her “possessed.” Kids said she was “mean.” She didn’t coo, didn’t giggle, didn’t sell. Within a year, Blythe disappeared from stores, vanished from the mainstream, remembered mostly as a failed experiment in doll design.

At this point, Blythe could have been a footnote — a weird toy that didn’t make it. But the thing about strange girls, whether human or plastic, is that they don’t stay buried long.

“Barbie sold you a dream house. Blythe sold you a blank stare and let you fill in the rest.”

Part II: Gina Garan and the Art of Resurrection

Flash forward to the late ’90s, New York photographer Gina Garan stumbled onto a vintage Blythe doll at a flea market. She started photographing her everywhere — in parks, on city streets, in elaborate costumes. The doll’s eerie, expressive face translated shockingly well on film.

In 2000, Garan releases This Is Blythe, a photobook that changes everything.

The images are strange, cinematic, and completely un-Barbie. Blythe doesn’t smile; she haunts. She doesn’t pose; she performs. The art world takes notice — and so does Japan.

When Japanese toy company Takara considers bringing Blythe back, they partner with Cross World Connections (CWC), a Tokyo creative agency led by Junko Wong. If Garan resurrected Blythe, Wong gave her a whole new personality.

Wong saw Blythe not as a toy but as a concept — a blank slate for storytelling, art, and fashion. She convinced Takara to relaunch her not for kids, but for adults — especially young women steeped in Japan’s booming kawaii and Harajuku cultures. Under Wong’s creative direction, each new release came with a theme, an outfit, and a narrative. Blythe wasn’t “playtime”; she was collectible culture. She became part of the kawaii-culture-meets-haunted-doll aesthetic that Japan does so well.

Wong also spearheaded collaborations with major fashion brands, curated gallery exhibitions, and nurtured a creative community of designers, photographers, and fans. Under her direction, Blythe became a global art object, blurring the boundaries between toy, muse, and medium.

Cult Following:

Suddenly, Blythe was everywhere: in magazines, exhibitions, collaborations with fashion designers. But most importantly, she became a DIY phenomenon.

“Owning a Blythe is like joining a coven: once you’re in, you see her everywhere.”

Unlike Barbie, who comes with pre-scripted identities (Doctor Barbie, Malibu Barbie, President Barbie), Blythe was a blank canvas. Her oversized head made her easy to customize. Her surreal look demanded creative interpretation. Women started sewing outfits, repainting faces, and photographing her like a living muse.

Check out this vintage interview with Gina published in ‘Colouring Outside the Lines‘ from 2008.

Timeline: The Life (and Afterlife) of Blythe

1972 – Birth & Death – Kenner releases Blythe, designed by Allison Katzman. Her click-change eyes freak everyone out. Sales tank. She’s discontinued within a year.

1980s–1990s – The Wilderness Years – Blythe becomes a thrift-store curiosity, quietly traded by oddball collectors.

1997 – Gina Garan Finds Her Muse – A vintage doll, a camera, and a lot of curiosity spark a creative obsession.

2000 – This Is Blythe – Garan’s photobook reframes Blythe as art and lands on the desks of Japanese designers.

2001 – Japanese Relaunch – Takara and Junko Wong’s CWC reissue Blythe as a collectible for adults.

2000s – Cult Status – From Alexander McQueen runways to art exhibits, Blythe becomes a fashion muse.

2010s–Present – The DIY Movement – Blythe rules Etsy, Instagram, and collector forums. Custom dolls sell for thousands. Diversity improves, but debates continue.

Part III: The Feminist Potential of Play

Why does this weird little doll strike such a nerve with feminist makers, artists, and zinesters?

Rejection of Perfection:

Blythe isn’t classically beautiful. Her weirdness is the point. Loving her is an act of embracing what’s off, awkward, and uncanny. For women told to fit into narrow standards of beauty, this feels radical.

DIY Culture:

Blythe’s fanbase thrives on customizing, sewing, repainting, and photographing. It’s less about buying into a brand narrative and more about hacking it for personal expression. This aligns with feminist craft traditions and zine culture.

Community:

Blythe collectors built forums, meet-ups, swaps, and exhibitions long before Instagram. Many describe it as a safe, mostly female-dominated space where art, play, and rebellion mix.

Critique of Consumerism:

While Blythe is still a commercial product, the way her community uses her disrupts the typical “buy more, look pretty” script of dolls. She becomes raw material for storytelling, not a finished product.

“Every feminist reclamation starts the same way: take what they threw away, make it our own.”

Part IV: The Problematic Side

Of course, no doll is free from baggage. Blythe has her share of contradictions — the very tensions that make her both a feminist muse and a feminist dilemma. She’s a site of contradiction, where empowerment and exploitation coexist on the same glossy surface.

On one hand, Blythe represents a kind of weird beauty that challenges narrow doll standards by embracing the strange, uncanny, and offbeat. Her enormous eyes and unearthly proportions reject the polished symmetry of traditional fashion dolls. For collectors and artists, she symbolizes the right to be awkward, eerie, and uncontained.

She challenges the plastic ideals of the toy aisle, but still lives inside the same system that sells beauty. Her strangeness is radical, yet profitable.

She also embodies the power of DIY culture — women customizing, hacking, repainting, sewing, and photographing her into existence again and again. The Blythe community thrives on this creative autonomy, turning a mass-produced toy into an individualized work of art. In doing so, it fosters a global network of mostly female collectors and artists, linked through forums, meet-ups, and online exhibitions that celebrate collaboration over consumption. But that very creativity is now part of the brand’s marketing.

Blythe is also a textbook example of reappropriation — transforming a failed consumer product into a tool of self-expression. What began as a corporate misfire has become a feminist act of reclamation: taking something discarded by the mainstream and making it meaningful on one’s own terms.

Her oversized head doesn’t erase the realities of body politics — beneath that cosmic head, her body is still the impossibly thin “ideal” that has dominated doll design for decades.

For much of her history, representation issues have persisted too; Blythe’s skin tones were overwhelmingly white or light until very recently, and even now, diversity often feels tokenistic rather than transformative.

Then there’s the question of corporate profit. While women perform the creative labour that keeps the Blythe community alive — customizing, photographing, and promoting her — the financial benefits flow upward to Hasbro and Takara. Like so much of women’s subcultural creativity, the grassroots energy gets monetized by the very systems it tries to subvert.

Finally, there’s the lingering ambivalence of “creepy-cute.” Her wide-eyed innocence both mocks and mirrors the infantilization of women. Some see Blythe’s eerie childlike features as a commentary on femininity — unsettling, uncanny, a refusal to be conventionally beautiful. Others see her as another version of the pretty, passive girl, just rendered through irony.

In other words, Blythe is not an uncomplicated feminist hero. She is both muse and mirror — revealing the contradictions of feminist aesthetics, consumer culture, and play itself.

And maybe that’s what makes her so powerful. She’s a contested object — a perfect mess of contradictions, irony, and longing. She’s what happens when feminism meets consumerism and both decide to stay messy (just like us).

“She’s not pretty. She’s powerful because she’s strange.”

Part V: Blythe in Pop and Subculture

Over the past two decades, Blythe has appeared everywhere:

- Fashion: Designers like Alexander McQueen and Issey Miyake have referenced Blythe. Limited-edition dolls wear runway-inspired outfits.

- Photography: Thousands of artists use Blythe in conceptual projects, zines, and digital art.

- Music and Media: Blythe occasionally surfaces in music videos, indie films, and advertisements, usually to signal strangeness or alternative femininity.

- Online Communities: Instagram, Etsy, and niche forums sustain massive subcultures of Blythe collectors. On Etsy, handmade Blythe outfits sell for hundreds of dollars. Customized dolls can fetch thousands.

For many women, buying or customizing a Blythe is less about the doll itself and more about joining a global network of creative rebellion.

Part VI: Blythe and Zine Culture — A Perfect Match

Here’s where She Zine readers will nod in recognition: Blythe and zine culture share DNA.

- Both are DIY platforms. Zines and Blythe dolls reject mass-media polish in favour of handmade imperfection.

- Both reject polish in favour of imperfection.

- Both thrive on community. Swaps, fairs, meet-ups, forums — the infrastructure is eerily similar.

- Both are feminist by use, not by origin. Neither zines nor Blythe dolls were originally created as feminist tools, but women made them so.

- Both embrace weirdness and give visual form to strangeness and refusal.

- Both live off photocopiers, sewing machines, and sheer nerve.

A zine about Blythe? It would practically write itself.

Part VII: What Blythe Teaches Us About Feminist Reclamation

Here’s the bigger picture — Blythe isn’t just a story about a doll.

She’s a microcosm of how women take the things culture discards and turn them into gold glitter and revolution.

- Take the Rejects: Things discarded by mainstream culture often become powerful tools in feminist hands (failed toys, thrifted clothes, abandoned spaces).

- Twist the Narrative: Instead of letting corporations define the meaning of a doll, women create new meanings through play, craft, and storytelling.

- Community as Resistance: Individual dolls become excuses for collective creativity, connection, and visibility.

Blythe reminds us that feminism isn’t only about protests or policy. It’s also about the tiny acts of reclamation that say: We decide what matters. We decide what beauty looks like. We decide what play can mean.

The Stare That Stays With You

Fifty years after her “failure,” Blythe is still here. Not because a corporation insisted, but because women made her matter.

She’s creepy, beautiful, weird, and hard to pin down — just like the feminist communities who gave her a second life.

“Blythe is proof that the weird girl always comes back stronger.”

Blythe dolls don’t come with a neat moral. They’re not unproblematic. But they show us something vital: that even the strangest, most rejected objects can become sites of radical play and feminist power when reimagined through our own eyes.

And maybe that’s the lesson Blythe offers with her giant, shifting gaze. She doesn’t just look at us. She asks us to look back — to see beauty where others saw failure, to claim what was dismissed, and to make it our own.

→ Got a Blythe? Show us her best weird angle with #TheFutureIsHandmade.

→ Sign up for The Edit to get zine-worthy stories in your inbox.

Sources:

This Is Blythe – “Who Created Blythe Dolls?”, Wikipedia – Blythe (doll), Blythopia – “All About Blythe”, The Blythe Guide – “History of Blythe”

AXO (she/her) is a multidisciplinary creator, editor, and builder of feminist media ecosystems based in Toronto. She is the founder of She Zine Mag, Side Project Distro, BBLGM Club, and several other projects under the AXO&Co umbrella — each rooted in DIY culture, creative rebellion, and community care. Her work explores the intersection of craft, technology, and consciousness, with an emphasis on handmade ethics, neurodivergent creativity, and the politics of making. She is an advocate for accessible creativity and the power of small-scale cultural production to spark social change. Her practice merges punk, print, and digital media while refusing to separate the emotional from the practical. Above all, her work invites others to build creative lives that are thoughtful, defiant, and deeply handmade.