As Told by a Certified Weirdo, Former Cabbage Patch Cult Member, and Defender of Lumpy Icons

Lumpy Icons

In the world of toys, few products have managed to masquerade as a social movement quite like the Cabbage Patch Kids. Before they were cluttering thrift store shelves or becoming eBay oddities, they were the hottest toy of the 1980s — and not just because they were cute. No, Cabbage Patch Kids weren’t just dolls. They were orphans in need of homes. You didn’t buy one — you adopted it.

And if that sounds like marketing genius wrapped in a soft-bodied, big-headed package, that’s because it was.

They had pudgy cheeks, dimpled knees, yarn hair in impossible colours, and names like Melvin Cornelius or Eliza Fern. They smelled faintly of plastic and baby powder. Some of them blinked. Others giggled. But no matter how many times you brushed their polyester hair or read their “adoption” papers, one truth remained: Cabbage Patch Kids were weird. Like, weird weird.

And yet, we loved them.

Maybe you had one. Maybe you wanted one so badly it physically hurt. Maybe you stared at them in the Sears catalogue with the reverence of a pilgrim. Or maybe you, like a lot of us, found them sort of unsettling — their uncanny baby faces frozen in manufactured innocence, as if something inside them might blink when you’re not looking.

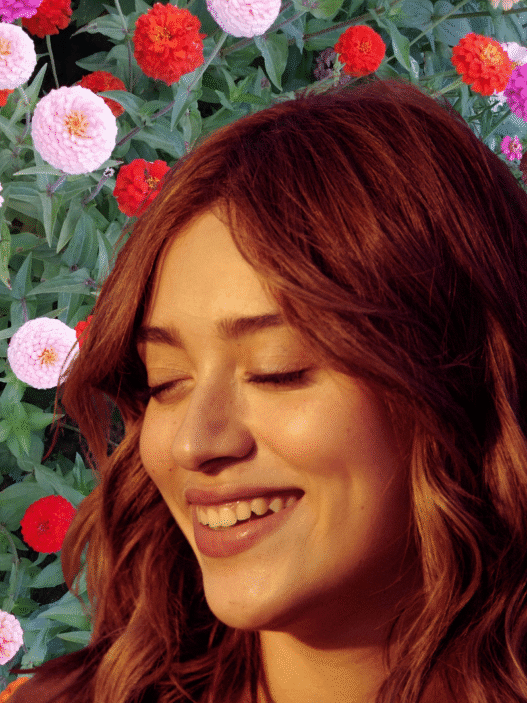

I won mine in a raffle at my pre-school. Aside from my dog dying when I was three, winning that cabbage patch doll was my earliest memory.

Let’s be honest: the Cabbage Patch Kids were never “cute” in the traditional sense. They were lumpy and odd and often mismatched. Their faces looked more like elderly babies than actual toddlers. But that offbeat aesthetic was the charm. At a time when most dolls aimed for either hyper-glamour (Barbie) or high realism (American Girl), the Cabbage Patch Kids carved out a third lane: soft, surreal, and emotionally complicated.

And that might be the real reason they became icons.

“They wrapped consumerism in cabbage leaves and sold it to us as love.”

Adoption Papers, Capitalism, and Emotional Manipulation

Launched into the mainstream in 1983, Cabbage Patch Kids weren’t the first dolls to come with backstories. But they were the first mass-produced toys to use adoption as both a narrative and a transaction. Each doll came with an official “adoption certificate” bearing its unique name and birthdate, along with solemn instructions to promise to love and care for it forever.

In other words: a contract. A bond. A commitment that somehow made a $30 toy feel like a sacred obligation. Kids weren’t just consumers — they were caretakers. Parents weren’t just spending money — they were facilitating a life event.

Underneath the cabbage leaves and feel-good storylines, it was pure marketing brilliance. By framing a purchase as an adoption, Cabbage Patch Kids turned commerce into a rite of passage. No one was “spoiling” their kid — they were welcoming a new member into the family. Retail therapy had never felt so morally justified.

Soft Power in a Soft Body

The power of the Cabbage Patch Kids wasn’t in their design — let’s be real, they were weird-looking babies with chubby cheeks and questionable fashion sense. Their power was in the ritual surrounding them. The story of being born in a magical garden and adopted by a loving child blurred the line between fantasy and commerce.

It was one of the earliest examples of emotional branding aimed directly at children. Not unlike Build-A-Bear decades later, the process mattered more than the product. And it planted an early seed (pun fully intended) about what makes us form attachments: narrative, not function.

The dolls weren’t personalized by the buyer — they came preloaded with names and identities, as if the child were entering the world of the toy, not the other way around. It was ownership dressed as responsibility. Love packaged with plastic.

“The dolls weren’t trying to teach you how to be pretty. They taught you how to nurture something imperfect.”

Ugly-Cute and Early Identity Play

There’s something fascinating about how Cabbage Patch Kids disrupted the way children related to dolls. Most dolls projected an aspirational ideal — beautiful, perfect, grown-up. Cabbage Patch Kids were messy and strange. Some had glasses, freckles, buck teeth, or bald heads. They weren’t trying to teach you how to be pretty. They taught you how to nurture something imperfect, and to see beauty in weirdness.

It was a proto-lesson in empathy. A gateway to identity play. For many kids, these dolls were their first experience with naming, caring, projecting feelings onto something soft and blank and just alive enough. There’s a reason so many queer adults today say they loved their Cabbage Patch Kids — and it’s not just nostalgia. These dolls offered a space for emotional rehearsal that didn’t rely on binary beauty standards or social scripts.

Black Cabbage Patch Kids Were Revolutionary — Even If the Brand Didn’t Know It

Before Black Barbie got her due. Before American Girl introduced Addy. Before diversity in toys was the subject of thinkpieces and TED Talks — there were the Black Cabbage Patch Kids.

They didn’t arrive with much fanfare. They weren’t heavily promoted. But when they showed up in the toy aisle, something seismic shifted. For thousands of Black kids across North America, it was the first time they saw a doll that looked like them on the same shelf — and in the same box — as the white ones. No “ethnic” section. No weirdly separate branding. Just a soft-bodied, round-cheeked little friend with textured hair and brown skin, waiting to be adopted.

It wasn’t perfect. But it was radical.

“Representation wasn’t in the marketing — it was in the reception.”

Representation Hits Different in Childhood

If you grew up in a world where your race was rarely reflected in media or products, seeing a toy that looked like you wasn’t just cool — it was a tectonic shift. And for many Black children in the 1980s, Cabbage Patch Kids were that shift. You could choose a doll who shared your skin tone. You could receive an adoption certificate with a Black baby’s name on it. You could cradle something that felt like it belonged to you.

And while that may sound basic in 2025, it wasn’t in 1983.

Representation in children’s toys is often minimized or treated as an afterthought — but it’s foundational. Dolls are stand-ins. They are practice bodies, emotion-training dummies, mirrors we hold up to the world. When a kid only sees whiteness reflected back, that absence becomes part of the script. Black Cabbage Patch Kids quietly rewrote that.

“Cabbage Patch Kids weren’t just dolls. They were emotional training wheels.”

Moms, Memory, and Cultural Impact

Ask around in Black communities, and you’ll hear a common refrain: “My mom made sure I got a Black doll.” There was something deeply intentional about it — a tiny act of resistance in a very white toy culture. For many parents, buying a Black Cabbage Patch Kid wasn’t just a cute Christmas present; it was an act of affirmation. A way of saying, You are seen. You are valid. You are worthy of joy and care and play.

And that matters. Especially when the rest of the media world tells you the opposite.

These dolls are etched in memory not because they were trendy, but because they were meaningful. They carried the weight of a thousand bedtime stories, hair braiding sessions, and tea parties where every chair at the table meant something.

The Brand Didn’t Deserve the Praise — But the Impact Remains

Let’s not give Coleco or Xavier Roberts too much credit. The Cabbage Patch Kids brand never made diversity a pillar of its identity. There were no public statements. No awareness campaigns. No celebratory ads in Ebony or Jet. The inclusion of non-white dolls was quiet, transactional, and ultimately underexplored.

But that doesn’t mean the dolls didn’t do their work. Like so many acts of representation in the 80s and 90s, the meaning wasn’t in the marketing — it was in the reception. In the way kids gravitated toward dolls that looked like them. In the way parents demanded them. In the quiet revolution of the playroom.

They Weren’t Just Dolls — They Were Proof

In the end, the Black Cabbage Patch Kids weren’t political because the brand made them that way. They were political because existence is political when the default is whiteness. They were revolutionary because they showed up on shelves where they weren’t expected. And they were powerful because they were held, named, and loved by kids who had been waiting for their reflection.

These weird little cabbage-born babies weren’t just toys. For some of us, they were the first time we felt seen in a store.

And honestly? That’s more than most brands can say.

Between Cute and Creepy: The Uncanny Valley of Childhood

Of course, that uncanny energy wasn’t lost on anyone. There’s a reason they’ve appeared in horror spoofs and campy 80s films. There’s something about their eyes — their unblinking, spherical stare — that makes them feel half alive. Combine that with their birth story (sprouted from the dirt like some Victorian changeling fantasy), and you’ve got the perfect recipe for pop culture hauntings.

But maybe that creepiness was part of the draw. The best childhood toys always sit in that liminal space between comfort and fear. They’re portals — not just to imagination, but to early understandings of life, death, care, rejection, and belonging. The Cabbage Patch Kids didn’t try to be perfect. And in their not-perfectness, they became mirrors for every kid who felt weird, or awkward, or like they didn’t quite belong either.

Weird Girls Raised by Weird Dolls

The Cabbage Patch Kids weren’t meant to spark a movement — but weird girls everywhere made them revolutionary. We loved them because they were lumpy. Because they were strange. Because they looked like they’d been hit with a charm spell and a frying pan. They weren’t pretty in the way dolls were supposed to be. And neither were we. That made them ours.

Behind the pastel packaging and adoption papers, we were learning something radical: love doesn’t have to follow a script. These dolls weren’t about aspiration — they were about attachment. Not about becoming perfect — but protecting what’s already imperfect. That’s the kind of emotional training the New Girl Army is built on. Quiet rituals. Soft rebellion. Choosing the weird doll on purpose because she looked like someone who might understand you.

And yeah, we were being sold something. It was capitalism wrapped in cabbage leaves. But even within that system, we carved out a different story. We stitched punk patches on their OshKosh. We gave them names that didn’t come on the certificate. We made them our own. In a world that told us to want Barbie, we chose something uncanny. Something that blinked wrong and smelled like plastic and still felt like love. That’s how creative rebellion starts — not with a manifesto, but with a strange little doll you swear could wink.

Urban Legends, Ghost Stories, and Cursed Cabbage Patch Dolls

They were supposed to be cute. Wholesome, even. Born from magical cabbages and adopted into loving homes, the Cabbage Patch Kids were marketed as the softest, sweetest antidote to Barbie glam and G.I. Joe grit.

But somewhere between their factory-made dimples and plastic-scented yarn hair, something… shifted.

Maybe it was the way their eyes never blinked. Or how they always seemed a little too sentient. Or maybe it was just the sheer oddness of the whole “grown in the dirt and adopted” origin story. Whatever it was, it didn’t take long for the whispers to start:

Cabbage Patch Kids are cursed.

A Garden Full of Ghost Stories

The ‘80s were a breeding ground for playground lore, and the Cabbage Patch Kids were ripe for urban legends. The most famous tale? That they came to life at night. Not in the cute Toy Story way — more like “standing silently at the foot of your bed” way.

Parents would find dolls moved from where they were left. Kids swore they saw their doll’s mouth move. One especially widespread rumour claimed a boy in Ohio had been strangled in his sleep by the doll’s fabric arm. The truth? Debunked. The vibes? Still off.

These dolls didn’t just look weird — they felt weird. And kids are exceptionally good at picking up on the uncanny.

Blame the Eyes (and the Silence)

There’s something about the Cabbage Patch stare — wide, glassy, unblinking — that hits the uncanny valley hard. Unlike other dolls that winked, giggled, or had blinking eyelids, these ones just watched.

They were also quiet. No batteries. No voice boxes. Just silence. And yet, many kids reported “hearing” them. Imagining voices. Receiving telepathic messages (usually warnings or guilt trips).

Of course, much of this is projection — kids creating personality from a blank slate. But paired with the bizarre lore and culty adoption rituals, it was enough to make more than a few kids shove their beloved doll in the closet and sleep with the light on.

Satanic Panic’s Favourite Doll?

Let’s not forget the cultural context. The Cabbage Patch boom hit right in the middle of the Satanic Panic. Adults were already convinced that Dungeons & Dragons, heavy metal, and scented markers were corrupting the youth.

Cabbage Patch Kids didn’t escape the scrutiny. Some conservative groups even claimed the dolls promoted “witchcraft” through their magical garden birth and “adoption ceremonies.” A few televangelists got especially weird about it — one even insisted the dolls were vessels for demonic possession.

The fact that the dolls came with “adoption papers” only made things creepier. Kids were encouraged to sign contracts. That, for some overly superstitious parents, looked suspiciously like a pact.

Real-Life “Hauntings” and Collector Weirdness

Today, the haunted Cabbage Patch legend has grown thanks to YouTube, TikTok, and collectors who specialize in the strange and cursed. One Reddit user posted a video of their vintage Cabbage Patch Kid turning its head “on its own.” Another swore theirs whispered during a thunderstorm.

There are entire TikTok accounts dedicated to “haunted dolls,” with Cabbage Patch Kids getting prime screen time. Some collectors even want the creepy ones — claiming they can feel different energy from certain dolls. (Is it a haunted vibe or just polyester that’s been in a damp box for 30 years? Who’s to say?)

Why We Love Creepy Dolls (Especially This One)

So why are we still talking about haunted Cabbage Patch Kids in 2025? Maybe it’s because we never fully trusted them. Maybe it’s because the whole idea of mass-produced children, grown in soil and shipped to department stores, was inherently unhinged.

Or maybe, just maybe, because it’s fun.

The horror-tinged nostalgia has become part of the doll’s legacy. Much like Furbies, Chucky, or those terrifying porcelain dolls your grandma swore were “beautiful,” the Cabbage Patch Kids live on as objects of affection and discomfort. And honestly? That’s kind of iconic.

Cute, Creepy, and Culturally Undead

Whether you see them as cursed or cuddly, the truth is this: Cabbage Patch Kids were always more than just dolls. They were ritual objects disguised as toys. Cultural artefacts in OshKosh overalls. And for some of us, lowkey haunted relics from childhood.

So go ahead — dig yours out of storage this Halloween. Put her on the shelf. See if she moves. (Just… maybe don’t read the adoption certificate out loud at midnight. You know, just in case.)

Representation as a Quiet Rebellion

Let’s be clear: Coleco didn’t exactly lead the diversity charge. The inclusion of Black, Asian, and other racially diverse dolls in the Cabbage Patch line wasn’t driven by a righteous sense of representation — it was driven by market potential. Xavier Roberts didn’t have a DEI advisory board in his Georgia toy workshop. But whether intentional or not, the effect was powerful.

Unlike many toys of the 80s that tokenized or exotified non-white characters, the Cabbage Patch Kids didn’t lean into stereotypes. The dolls were essentially identical in shape and design — chubby cheeks, goofy smiles, often wearing identical outfits — just with different skin tones and hair textures. This parity mattered.

It told kids: your version of the doll isn’t the other one. It’s just one of many. Not a variation, a presence.

Manufactured Scarcity, Manufactured Chaos

It’s impossible to talk about the Cabbage Patch Kids adoption craze without mentioning The Riot. You know the one — where grown adults trampled each other in department stores, ripped dolls from strangers’ hands, and formed endless lines outside toy shops like they were selling backstage passes to Madonna.

This wasn’t an accident. Coleco, the company responsible for the toy’s initial mass production, knew exactly what they were doing. By creating artificial scarcity and tightly controlling inventory, they turned Cabbage Patch Kids into the Tickle Me Elmo of their era — but with better names and adoption papers.

That scarcity didn’t just fuel demand; it created a sense of urgency and moral panic. “What if my kid doesn’t get to adopt one?” That wasn’t just a missed birthday present — that was a maternal failure. A generational trauma. A playground status disaster.

Cabbage Patch Kids weren’t just a fad — they were a cultural event. They triggered riots in department stores. They appeared on talk shows. They spawned knockoffs, lawsuits, cartoons, and collector clubs. At their peak, they were everywhere. And now? They’re thrift store darlings. Instagram nostalgia bait. Weird little relics from a time when toys had origin stories and adoption paperwork.

But they’re also something more: a reminder that charm doesn’t have to be polished. That weirdness is often the root of love. And that being adored for your oddness is a kind of quiet revolution.

So if you ever see one at a garage sale — maybe with yarn pigtails and a crooked smile — go ahead and pick her up. There’s still something strangely radical about a doll that was never meant to be pretty.

Just unforgettable.

A Lesson in Childhood Consumerism

It’s easy to laugh now — the shopping riots, the spin-off cartoons, the weird snack tie-ins. But beneath the cabbage leaves and chaos, the Cabbage Patch Kids were teaching us something a little darker: how to be consumers with feelings.

They weren’t just toys; they were training. We were handed contracts disguised as adoption papers. We learned that naming something made it matter. That love could be pre-packaged. That commitment came with a price tag — and it was non-refundable.

This was emotional branding before it had a name. Cabbage Patch Kids weren’t aspirational like Barbie or educational like LeapFrog. They were sentimental objects that manipulated our attachment systems. They whispered: This is yours, and it needs you. And we believed them.

In hindsight, it was genius — and a little sinister. The dolls weren’t designed to make you want one. They were designed to make you feel bad if you didn’t have one. That’s not just marketing. That’s weaponized affection.

And it worked.

Welcome to the Family (Now Please Pay)

In the end, the Cabbage Patch Kids were many things: beloved companions, status symbols, emotional training wheels, and tiny capitalist Trojan horses. They wrapped consumerism in cabbage leaves and sold it to us as love.

And we ate.. it.. up!

Even now, decades later, the legacy of the “adopt don’t shop” toy lives on — in limited edition releases, resale markets, and the broader culture of collectibles and identity-based branding. We’re still buying things that promise to love us back. Still looking for stories that make our stuff mean something.

Turns out, the garden was never just for kids.

Cabbage Patch Kids Around the Internet

While researching this piece, I stumbled into a strange and wonderful corner of the internet — part nostalgia trip, part morbid curiosity, and honestly? Kind of amazing. The Cabbage Patch Kid community is still very much alive, with collectors, horror theorists, and wholesome weirdos keeping the magic (and chaos) going.

One of the gems I found was a 16-minute piece by Vice from way back in April 2015. If I’ve piqued your interest in these lumpy little legends, it’s absolutely worth a watch.

They weren’t just dolls — they were the first weird little generals in our girl gang revolution.

JOIN THE NEW GIRL ARMY

We were raised by weird dolls, messy closets, and stories that didn’t make sense until they did. If you’re still carrying that soft rebellion in your pocket — welcome home.

Subscribe to The Edit for more stories like this

💌 Pitch us your weirdest toy story

🧷 Tell us what your doll was named. We’re collecting them. Seriously.

→ Subscribe to The Edit

→ Pitch Us a Piece

→ Follow @SheZineMag

You want to make the experience even more bizarre? Cue up The Cabbage Patch Kids: All-Time Favourites — an album so cursedly chipper, it’ll have you questioning everything you thought you knew about childhood joy.

AXO (she/her) is a multidisciplinary creator, editor, and builder of feminist media ecosystems based in Toronto. She is the founder of She Zine Mag, Side Project Distro, BBLGM Club, and several other projects under the AXO&Co umbrella — each rooted in DIY culture, creative rebellion, and community care. Her work explores the intersection of craft, technology, and consciousness, with an emphasis on handmade ethics, neurodivergent creativity, and the politics of making. She is an advocate for accessible creativity and the power of small-scale cultural production to spark social change. Her practice merges punk, print, and digital media while refusing to separate the emotional from the practical. Above all, her work invites others to build creative lives that are thoughtful, defiant, and deeply handmade.

Lumpy Icons

Lumpy Icons