Content/Trigger Warning:

This article discusses depression, mental illness, misogyny in gaming, doxxing, online harassment, death threats, and sexual violence threats. It also references #GamerGate and the coordinated abuse of women and marginalised creators in digital spaces.

This is the story of Zoë Quinn, or what happens when a woman makes a video game about depression.

It starts, as these things often do, in a quiet, half-lit room. A computer screen. A cursor blinking. A person who’s been through hell, trying to make sense of it all. The feeling isn’t cinematic—it’s static. The hum of electronics. The weight of memories. And in that stillness, Zoë Quinn started building something radical: a game that tried to explain what it feels like to be unable to function.

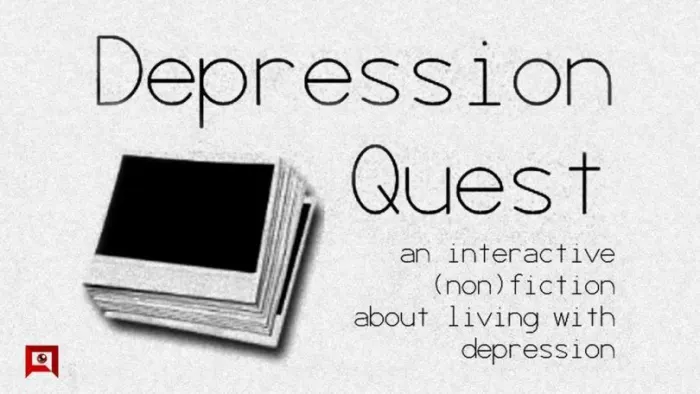

In 2013, Quinn released Depression Quest, a browser-based interactive fiction game that dropped like a spark into dry kindling. It was raw and quiet and heavy. No dramatic shootouts or boss fights. No points to earn. Just words on a screen and a suffocating sense of helplessness. Players navigated the experience of someone struggling with depression, making everyday choices—most of which were unavailable, greyed out by the game’s mechanics. Not because the protagonist didn’t want to engage, but because they couldn’t.

The game’s goal was simple: let people feel what it’s like when you know what to do but you can’t do it. It was both a mirror and a message. A resource for those silently struggling. A tool to build empathy in those who weren’t. It was quiet and brave—and it shouldn’t have needed to be revolutionary.

But it was.

What It Felt Like to Play

Depression Quest placed players inside a disjointed version of everyday life: you wake up, you work, you talk to friends—or you try to. But certain dialogue choices and actions are blocked out, reflecting the paralysing nature of clinical depression. It was uncomfortable. Not just because of the subject matter, but because it refused to entertain in a traditional sense. The game asked for vulnerability. For patience. It didn’t reward you. It just was.

Critics praised it for its emotional clarity. Some gamers, however, felt deeply threatened—not by the gameplay, but by what it represented: a shift toward games as storytelling tools, as therapy, as art. A shift toward access—to game creation, to narrative ownership, to voices that had long been pushed out.

This Isn’t Just a Story About a Game

It’s about who gets to make games. Who gets to be visible. And who gets punished for doing both.

Zoë Quinn wasn’t a studio-backed prodigy. They were a DIY game maker, a community-driven creative who found a voice through Twine—a simple game engine that allowed creators to build interactive stories without coding experience. They were part of a wider movement of queer, trans, and marginalised creators pushing games into personal territory: trauma, identity, grief, love, rage.

When Depression Quest started getting recognition—coverage on gaming sites, mentions in mental health forums—it disrupted something sacred to a certain slice of the gaming world: their idea of who gets to take up space.

The pushback was instant and vicious.

Weaponising a Breakup: The Spark of #GamerGate

In August 2014, Zoë Quinn’s ex-boyfriend, Eron Gjoni, published a sprawling blog post titled The Zoe Post. Framed as a personal account of their breakup, the post detailed private aspects of their relationship and accused Quinn of infidelity. But it didn’t stop there. Gjoni implied that Quinn had been romantically involved with a journalist from Kotaku and suggested that this relationship may have led to the favourable media coverage of Depression Quest.

The post went viral almost immediately—not out of concern for journalistic ethics, but because it handed certain corners of the internet exactly what they’d been waiting for: a pretext. A scapegoat. A spark in a room full of gasoline.

The accusations were unsubstantiated. No evidence of special treatment ever surfaced. In fact, the journalist in question never reviewed Depression Quest at all. But the facts didn’t matter. The narrative had already taken hold.

What began as a deeply personal act of retaliation grew into something far bigger and more dangerous—a coordinated, global harassment campaign under the banner of what would soon become known as #GamerGate.

Framed as a movement about “ethics in game journalism,” #GamerGate quickly revealed its true face: a misogynist backlash disguised as media critique. The blog post became an excuse to rage against “fake gamer girls,” “SJWs,” and anyone who challenged the dominant culture of gaming. Quinn’s personal information was posted online. Their family and friends were targeted. They received death and rape threats on a daily basis. Bomb threats were sent to venues where they were scheduled to speak. They had to leave their home. More than once.

And still, much of the broader gaming community stayed silent—or worse, egged it on.

Quinn, along with other figures like Anita Sarkeesian and Brianna Wu, were thrust into the public eye—not by choice, but by force. They were dehumanised, reduced to clickbait, and made into symbols.

But they didn’t disappear.

The Fallout

Quinn’s life was upended. They moved homes multiple times, lived out of suitcases, and cut off much of their public presence. The trauma was both acute and ambient—a daily background radiation of stress and fear.

And yet, they continued to make. To speak. To document what was happening not just to them, but to a generation of creators being chased offline.

Crash Override, their memoir, detailed it all—part personal narrative, part guidebook for surviving digital harassment. It wasn’t just catharsis. It was a call to arms.

Where Zoë Quinn Is Today

In the aftermath of #GamerGate, Zoë Quinn became more than a game developer. They became an advocate, a mentor, and a reluctant pioneer of digital resistance. They co-founded the Crash Override Network, an organization that supported victims of online abuse and worked with companies like Twitter and Tumblr to improve safety protocols. Though the initiative closed in 2018, its influence persists.

Quinn never stopped creating. They’ve gone on to write comics, build new games, and experiment with storytelling formats. They’re known not only for their narrative design work but for their passion for physical fabrication—particularly for creating theatrical props, fantasy armour, and animatronics that blend robotics and art.

Their creative projects are extensions of the same ethos that built Depression Quest: the idea that art should feel, should challenge, should connect.

They’ve spoken at the United Nations about online violence. They’ve helped shape public understanding of how online harassment works—and how it can be stopped.

Their name is still invoked online, often as a punchline by reactionaries clinging to the past. But Quinn isn’t interested in those conversations anymore. They’re building something new. Weird. Personal. And punk as hell.

Quinn’s work has been praised in such outlets as Forbes, Wired, the Wall Street Journal, Kotaku, Paste, and GiantBomb. Since August 2014, even more mainstream media have taken note, including MSNBC, the New Yorker, the New York Times, Vice, Playboy, BusinessWeek, and BoingBoing, and the UK’s BBC, Guardian, and Telegraph. Fast Company recently named her the seventeenth Most Creative Person in Business for her work with Crash Override, and she appeared on Forbes’ 30 under 30 list.

— Hachette Book Group

Why This Still Matters

You might think this is old news. #GamerGate? That was 2014. Ancient history in internet time. But it wasn’t just a moment—it was a trial run. The tactics perfected against Quinn and others—coordinated harassment, doxxing, radicalisation through YouTube—laid the foundation for much of the digital toxicity we see today.

The same strategies are used to attack journalists, trans creators, politicians, and activists. The culture war didn’t end. It just moved platforms.

And the gaming industry? Still overwhelmingly white, male, and corporate. Still resistant to risk. Still slow to protect its most vulnerable creatives.

But that’s not the end of the story.

Documenting the Digital Battlefield

The 2024 documentary, The Antisocial Network: Memes to Mayhem, examines the evolution of online communities like 4chan and their tangible impacts on society. Through archival footage, the film revisits the #GamerGate controversy, featuring Zoë Quinn’s pivotal role in the discourse surrounding women in gaming. This documentary contextualizes the harassment Quinn faced within the broader narrative of internet culture’s complexities and its influence on real-world events. By highlighting these connections, the film emphasizes the enduring challenges that marginalized groups encounter in digital spaces.

The Future is Handmade

What Zoë Quinn represents is something radical in the digital age: the right to make your own weird little thing. To build games about sadness, identity, rage, and joy. To make art that doesn’t perform. That doesn’t sell out. That doesn’t need to.

In the wake of everything, what remains most striking isn’t the abuse Quinn endured. It’s the fact that Depression Quest exists at all. That in a culture obsessed with flash and dominance, someone made a glitchy little game about hopelessness—and dared to say that matters.

That’s not just brave. That’s transformative.

If we want a better internet—if we want a better anything—we have to remember what Quinn showed us: the monsters aren’t just in the code. They’re in the systems. The algorithms. The silence.

And we have to keep making noise. Even if our voices shake.

Even if the pixels glitch.

Even if it feels like no one’s listening.

Make the thing anyway.

Depression Quest has now been played by over 2 million people and is available for free download in the Steam game store.

Join the New Girl Army. We’re building a magazine from the margins — and we mean it when we say it’s yours, too.

→ Subscribe to The Edit

→ Submit Your Work

→ Follow @shezinemagazine

AXO (she/her) is a multidisciplinary creator, editor, and builder of feminist media ecosystems based in Toronto. She is the founder of She Zine Mag, Side Project Distro, BBLGM Club, and several other projects under the AXO&Co umbrella — each rooted in DIY culture, creative rebellion, and community care. Her work explores the intersection of craft, technology, and consciousness, with an emphasis on handmade ethics, neurodivergent creativity, and the politics of making. She is an advocate for accessible creativity and the power of small-scale cultural production to spark social change. Her practice merges punk, print, and digital media while refusing to separate the emotional from the practical. Above all, her work invites others to build creative lives that are thoughtful, defiant, and deeply handmade.